Friday, March 05, 2010

"Not all stimulus spending is created equal"

The thinking behind stimulus spending comes from economist John Maynard Keynes, who argued that amid rising unemployment, the government might as well bury money underground and let private companies dig it up, if that�s what it takes to create jobs and soften a recessionary shock. But even if you accept the theory, and what Keynes considered the �multiplier effect� of government spending (spending a dollar of government money creates more than one dollar in positive economic effects), not all stimulus spending is created equal, notes University of Alberta economist Bev Dahlby. Given that it costs Ottawa money to borrow the money it�s been spending (the Tories have forgiven themselves for running a predicted $56-billion deficit in the fiscal year just ending, claiming it was imperative to rescuing the economy), some stimulus projects may actually take more out of the economy than they put in. The difficulty, he says, is picking the right projects.

�It�s not a free lunch; you just can�t push money out the door,� Mr. Dahlby says. In a recent paper for the C.D. Howe Institute, Mr. Dahlby calculated benchmarks for how Ottawa should select stimulus projects; anything not delivering sufficient and rapid direct consumptive and productivity results is better left on the shelf.

But with such a wad to spend, in a short time, the government often lacks enough options to park funds properly, which is why we might end up with plainly non-stimulating spending like the IndyCar grant. While a �more measured and slower response� is required in planning spending, Mr. Dahlby says. �The problem with that is that it might mean that, effectively, the timing of the stimulus will be screwed up, because then most of the projects and the money will be coming out in fact when the economy is recovering.�

As I said in that article, the true answer is you never know. There are simply too many moving parts to think you can pin down the ceteris paribus exercise enough to say the stimulus created (or saved) X number of jobs. But Mr. Libin is quite correct in his closing sentence: "We may never know if the stimulus provided any real protection for the Canadian economy; we can be sure it at least provided comfort for our elected leaders." So too in the U.S.

Labels: economics

Mrs. S writes

For the past few months, I�ve been looking for a job. It�s a long, arduous process, and sometimes I wonder what it would take for someone to hire me. They would have to pay me a salary, Social Security, unemployment insurance and perhaps health coverage and retirement benefits.That's the start of her column today, which may have gotten more notice than the news report on last night's Economic Outlook. Good for her. I don't think it's just because she's married to an economist that she thinks her job prospects depend on potential employers making a profit.

Where do they get this money? Because I can make them more profitable, or at least support them in their efforts to become more profitable. And if I can�t do that, no employer would hire me unless they wanted to lose money.

I�m not alone. About 6.3 million Americans have been unemployed for more than six months, up from 2.7 million a year ago. There�s talk of another jobs stimulus bill. But if government creates jobs for me, it needs to pay those things. Where does it get the money to do this?

February unemployment: Obama just says snow

Obama, touring a small business in Arlington, Va., said that the 36,000 jobs lost last month was "actually better than expected" considering the massive snowstorms that devastated the East Coast.From the Hill. I'm sure he only had time to read the executive summary, but if you read the actual report it includes this:

But the president said the steady number also �shows that the measures we're taking to turn our economy around are having some impact.�

Major winter storms affected parts of the country during the February reference periods for the establishment and household surveys.That says to me that BLS does not think the storm greatly altered the employment data.

In the establishment survey, the reference period was the pay period including February 12th. In order for severe weather conditions to reduce the estimate of payroll employment, employees have to be off work for an entire pay period and not be paid for the time missed. About half of all workers in the payroll survey have a 2-week, semi-monthly, or monthly pay period. Workers who received pay for any part of the reference pay period, even one hour, are counted in the February payroll employment figures. While some persons may have been off payrolls during the survey reference period, some industries, such as those dealing with cleanup and repair activities, may have added workers.

In the household survey, the reference period was the calendar week of February 7-13. People who miss work for weather-related events are counted as employed whether or not they are paid for the time off.

Where you would see a real effect of the storm would be on hours worked, but the data has a half-hour decline for construction and not much else. The headline number for private sector hours worked declined by 0.1 hours, with a similar small drop in weekly earnings, even though hourly wages were up three cents.

There are no data on hours worked in the government sector in that report. But Diana Furchgott-Roth of the Hudson Institute notes that those government workers who were unable to work did not lose pay and weren't laid off. So they can't be in this number.

36,000 jobs lost is a bit better than the consensus of 50k, but 14,000 is certainly smaller than the margin of error or the size of the monthly revision. The January number was revised to -26,000 from -20,000, for example.

On the good news/bad news front, the household survey actually showed job gains in February, but also an increase in those that had left the labor force but still wanted a job. The suddenly-fashionable U-6 unemployment rate (including discouraged workers, marginally attached workers and those working part-time that would prefer full-time work) rose to 16.8% from 16.5% in January.

In that context, Obama also promised a zero unemployment rate:

Despite the relatively good news, Obama repeated his pledge that he �will not rest� until every American who wants a job has one.Good luck with that.

Labels: economics

Thursday, March 04, 2010

Bullard at SCSU

- He's unsurprisingly negative on the idea of a Federal Reserve audit. He estimates that his staff spends about 425,000 hours a year on auditing between internal controls, the Board of Governors, and the external audit from Deloitte. The GAO audit is in addition to that. His slide notes: "Additional audits are welcome, so long as they do not constitute political meddling." You know where I stand on this.

- I note a good point he made on political influence via appointments to the Fed. Governors have 14 year terms which are staggered; however, most governors do not stay for 14 years and replacements are only appointed to complete terms, not get their own 14 year term from the start. This has effectively shortened terms and increased political influence. I talked about this a little two years ago when Sen. Dodd held up appointments to the Federal Reserve, waiting for a Democrat to take the White House. Glad to see he picked that up.

- On regulation, he stated the common Federal Reserve line that the Fed had limited visibility of the financial crisis. Only 12% of of banks and 14% of financial assets were in institutions primarily regulated by the Fed in January 2007. The financial landscape has many institutions, and the Fed regulates only one of those. Yet it is lender-of-last resort to all. Many will scoff at this as a facile dodge of responsibility. But there are two points to be made: One, we can't use the term "the banks" to mean financial markets any more, since most financial firms aren't banks. Second, if the Fed actually could have controlled these institutions, why is the Congress debating how much additional authority to give the Fed?

- Every time I see this graph, I'm still surprised. I don't know why I am, but I am. While much of that will wind up, the part that represents agency MBS purchases, Bullard noted, will not. It's a big piece.

- I posed a question to him about whether the Federal Reserve's response to regulatory problems or to the financial crisis were influenced by the dual mandate the Fed has, vis-a-vis the sole mandate of the ECB or many other OECD central banks. He replied it did not -- they pretty much all behave the same way regardless of the mandate. He then ventured further to comment on whether the Fed should respond to asset bubbles. This has been a theme with him in the past, and he reiterated his view that the Fed has very limited tools to pre-empt bubbles.

Wednesday, March 03, 2010

Tell me if you've heard this one before

...they would have to more than double in order to pay for what will be spent under current law, insuring that future generations simply would not have the freedom and opportunity that Americans currently enjoy. According to CBO, by 2050, individual income tax rates would have to be increased by about 90 percent to finance the spending between then and now. By 2082, tax rates would have to more than double with a potential tax rate on the highest incomes of 88 percent. �Such tax rates would significantly reduce economic activity and would create serious problems with tax avoidance and tax evasion.This brings me a real sense of deja vu, as many years ago I was a research assistant to Prof. Craig Stubblebine at Claremont Men's College (now Claremont McKenna College.) Stubblebine was part of the early efforts in the late 1970s and early 1980s to get real spending limits on the Congress. (I arrived in Claremont in 1979, and worked with Prof. Stubblebine in 1981-83.) Known as S.J. Res 56 back then, it passed one chamber only to be shot down in the other chamber with much sleight of hand. They tried again later to get the amendment passed by attaching it to the Gramm Rudman Hollings bill, which Gramm at least supported including the constitutional provisions. But it missed a two-thirds passage by a single vote and was not included, and fervor died with passage of GRH.

(I'll note the spending limitation amendment now proposed -- SLA for short -- is not the same as what was tried thirty years ago. A balanced budget amendment was included in it, waivable by a 60% vote in each chamber. Taxes were limited as a share of national income. In some ways, that bill was closer to the Taxpayer Bill of Rights than is SLA, as its authors admit.)

While I doubt this bill will see the light of day in this Congress, the possibility that Republicans could take over the House of Representatives may make SLA a part of that party's platform for the elections. That will be a cheerful thing, but the 2/3 provision for constitutional change may make this not much more than advertising that that party is taking its spending problem more seriously. It's a good start, but it needs to do more to convince voters it has forsworn its past profligacy.

Labels: economics, it's the spending stupid, Republicans

Budget fun starts soon; questions abound

OK, that's all the politics I'll do. Here's two more detailed parts of it if you want to get your hands dirty.

There's the ongoing GAMC fight, and the full forecast tries to add some instruction on this issue. If you read the full report, much of the benefit to the budget was foreseeable from a federal program that eases Minnesota's cost of Medicare and Medicaid. You will not get that money next time around, so it will make the 2012-13 deficit look a bit worse. As we knew would be true, unallotment doesn't help you at all with the out-year estimates.

The $2.5 billion in spending reductions made through unallotment do notMMB's report says the entire amount of MinnCare needed to take care of those moved from GAMC is reflected in the budget at p. 53-54. Wonkier types should read that page very carefully. I am not positive this is right, but it makes some statements, like that of Rep. Larry Haws, look like it's working with incomplete information :

become permanent reductions that continue in FY 2012-13. The planning estimates include complete repayment of K-12 school aids deferred in FY 2010-11 ($1.163 billion) and no repayment of the K-12 property tax recognition shift ($564 million). The projections do not include reinstatement of funding for the General Assistance Medical Care (GAMC) program that was line-item vetoed in FY 2011. If continuation of the program at current levels were assumed, an additional $928 million would be required in the 2012-13 biennium.

The Legislative GAMC solution is more cost-effective and efficient than the Governor�s auto-enrollment plan that will drain the Health Care Access Fund to the point of bankruptcy and exacerbate the state�s budget deficit. Minnesotans can�t afford the Governor�s plan or his veto pen. The clock is ticking and the poorest of the poor and sickest of the sick need us to breathe parliamentary live back into the GAMC solution. I will encourage House leadership to bring people back to the table.Here's the problem, based on discussion with sources and on documents we can see. One reason this was vetoed was that the Legislature's solution, according to Gov. Pawlenty's veto letter, used $170 million of money that he had already designated to close off the deficit in the current biennium. It also cuts provider reimbursements (at least until the hospital lobby gets around to pressuring for that money in later legislation.) Then there's this $928 million in the budget document. I'm still working on other leads to see if someone can get this explained to me better, but that appears to be an extra billion in deficits over the next three years plus change. The transition to MinnCare appears to add $766 million between current and next biennium, so that's a savings. It looks like two gross figures to me, and the MinnCare one looks smaller. I'm open to being persuaded differently about that, but I think I'm right.

Revenues are a little down from November forecast because, while GDP growth has been adjusted up to 3% from 2.2% for 2010, they've cut just a bit the wage projection. Take a look at this passage from page 38:

Global Insight expects growth in U.S. wages and payroll employment in 2010 to be stronger than they factored into their November baseline forecast, while MMB�s outlook for Minnesota employment and wage growth in 2010 has weakened modestly.Lower wages drive a lower income tax forecast which makes the deficit larger. Tom Stinson is up here tomorrow for Winter Institute, and I intend to ask him about this sentence to get it clarified. Why would Minnesota's wage growth lag the nation's? I have some ideas why it might be true, but it's not my sentence and I'm not sure I would write something that strong. And they wrote this before data revisions from BLS and DEED came out yesterday. They note that the revisions might change their view. If the answer is at all interesting, I'll tell you Friday.

Monday, March 01, 2010

Guacamole and overhead bins

I can say it was an OK experience. Particularly given my recent trips with Delta, the seats were the same, the delays not too out of line (someone apparently "soiled" a carpet in the aisle, so they needed an extra 45 minutes to clean it) and the service passable. I would fly them again.

But there was one interesting part of the gateside experience. You are quite hassled about bringing bags on the plane, but we know that there's a tragedy of the commons problem there too (like Donald Marron's story linked above with guacamole) so you are limited in how much to take. But Frontier tries to get you down to just one bag that will go under the seat, where my legs like to go instead. So two or three times they ask for your bags, which go with all the other bags to the claims area when you land rather than picked up in skyway. This I do not like because I don't like waiting in baggage claim, and there's a greater likelihood (I think -- how do I know?) that it gets lost. So I decline.

After seating first class and their loyalty program fliers, they then invite those who only have a bag to go under the seat to board next. Basically you're mini-royalty. And at least on casual inspection, I think more people responded to the incentive to get on the plane before those like me who insisted on using the overhead bins. This did not upset me at all -- I am benefited by having their bags not compete for space with mine, and if letting them on first is the cost of this, so be it. And it appears that Frontier had found a margin along which it could change people's behavior.

Perhaps it would work -- I will let you have all the chips you want first, if you don't touch the guacamole. But maybe not because it's guac and guac is good.

Labels: Delta Airline sucks even more, economics, food, travel

How much stimulus was it?

We show that, statistically, the federal expenditure stimulus compensated for the fifty states� negative stimulus due to collapsing state expenditures. The sum of the federal (positive) and states (negative) fiscal expenditure stimulus, however, is close to zero.So the stimulus didn't work because the states had to cut spending because they couldn't borrow like the Federal government can. Because fiscal policy ground to a halt as administrations changed at the end of 2008, you had a short period in 2009 where pure fiscal policy (the discretionary part, and not related to transfer payments) was mildly contractionary. It's unclear what anyone could have done to prevent that, but it may have set up the early poor results of the stimulus package, whose effects couldn't have been expected to work until the second half of 2009.

...The figures reveal that during the crisis, state and local fiscal expenditures dropped from USD 1547 billion in real terms in 2008Q3 to USD 1545.5 billion in 2009Q3 while the federal fiscal expenditures rose from USD 991.6 billion to USD 1043.3 billion over the same period. The consolidated fiscal expenditures therefore rose from USD 2536.6 billion in real terms in 2008Q3 to USD 2585.5 billion in 2009Q3. Moreover, all the three series fell before rising � as the economy was in a tailspin in the first quarter of 2009, both federal and state fiscal expenditures were falling with it.

Taken in conjunction with these graphs, it may explain some. I think the note is good insofar as it makes the point without much in the way of judgment (one might think they would argue the stimulus was too small, but they close the paper instead with a caution about the effect of the debt overhang, which limits the size of fiscal expansion. I am still of the opinion that in the short run the stimulus was responsible for 500,000 jobs saved or created, give or take a million jobs. The long-run effects are even murkier.

Labels: economics

One eye on work, other on budget

So why St. Cloud? That's the subject of my talks this week. I'll have some notes posted over the next week or so on this question, so please stop back., but a fuller talk on this will have to wait until the St. Cloud MSA gets released in the 2007 Economic Census of Manufacturing, which is on rolling release through May -- Minnesota data is not yet up as of last night.State economist Tom Stinson warns, however, that the state is still losing jobs. The Twin Cities and St. Cloud experienced the worst job losses, while Rochester and southwestern Minnesota have fared better, he said.

Since the recession began, the state has lost 45,000 manufacturing jobs and 25 percent of construction employment.

"If you look at manufacturing and construction, you see some pretty dismal situations," Stinson said.

The state will begin adding jobs by March or April, he said.

Labels: economics

Medals per million

Canada is quite justifiably proud. But I was intrigued -- is it true that adjusted for population the Canadians had pulled off quite a feat? The population of Canada is actually closer to 33 million, for one thing (I was doing the math in my head and 20 million just felt small, so I went to look it up.) There are other countries in the medal table that are smaller. What if we adjusted medals for population?

Norway has a population of about 4.5 million (2009 levels), or less than 14% of Canada's. And yet it manages to win 23 medals compared to Canada's 26. Doesn't that count for something? China has a huge population, so that competition for the Olympic team is likely to be very strong. The US has a high per capita GDP. These smaller countries of Europe, however, with small populations, do very well. I tried the same graphs with just gold medals or with GDP rather than population, and you get approximately the same results. Also note I just looked at the top ten countries in the medals table. If you go down further you may find a small country that won one or two medals and would finish on this list.

BTW, that gold medal record the Canadians broke? It was shared between Russia and ... Norway. Matthew Futterman shows that even using historical models, Norway did very well this year.

(And if this post does not get a link from noted NARN Norgephile Mitch Berg, he has seen his last cigar.)

UPDATE: Prof. David Wall of the Geography Dept. here at SCSU sends along this graphic too:

A map of medals since the beginning of the Winter Olympics is similar.

Wednesday, February 24, 2010

While I'm in the car

On an unrelated point, if you are in St. Cloud tonight, Benjamin refers us to a debate about the existence of God. Seems well worth your time, as both debaters appear interesting. Thought I would get that advertised before I leave.

Labels: economics

Tuesday, February 23, 2010

Mopping up

Treasury anticipates that the balance in the Treasury's Supplementary Financing Account will increase from its current level of $5 billion to $200 billion. This will restore the SFP back to the level maintained between February and September 2009.This action will be completed over the next two months in the form of eight $25 billion, 56-day SFP bills. Starting tomorrow, SFP auctions will be held each Wednesday...

The purpose of this will be to provide a temporary draining of excess reserves from banks, replacing them with these relatively short notes. The Treasury doesn't keep the cash; it hoards it in the Fed's balance sheet (see item 33 here) until it the paper matures, then it repays it. At last report the banks held $1,119 billion in excess reserves, so this is not that big an adjustment. But if interest rates don't move very much over the next two months from tighter credit, it will be a sign that banks are not seeing great lending opportunities outside of Treasuries. And it will give us some indicator of what happens when the Fed starts issuing its own paper instead of needing Treasury's help.

(h/t: Donald Marron, who reminds us that the Treasury can only do this while it has room under the debt limit.)

Labels: economics, Federal Reserve

Put Fannie and Freddie on budget

Today, U.S. Representative Michele Bachmann (MN-06) took part in a press conference as a cosponsor of the Accurate Accounting of Fannie and Freddie Mac Act. The bill is aimed at instituting a proper and complete accounting for the Government-Sponsored Enterprises Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.The Obama Administration has been in the news this month with claims that Fannie and Freddie are not going to be that expensive. After projecting Treasury investments of $230 billion to prop up the two companies, the budget a few weeks ago said the investment would be $188 billion. Of that, about $97 billion is to be returned in dividends from the two firms by 2020. This does not count, alas, the $175 billion inserted into the firms by the Federal Reserve, nor the $1,250 billion of their debt -- mortgage-backed securities -- that the Fed has purchased. San Francisco Fed President Janet Yellen said yesterday that these purchases "were vital in preventing a complete financial breakdown," which might tell us Fan/Fred are still in some rough shape. I don't know that the legislation would count Fed contributions to Fan/Fred.

The Congressional Budget Office estimates that Fannie and Freddie added $291 billion to the federal deficit in 2009 and will cost an additional $389 billion to run over the next ten years. However, Fannie and Freddie are currently considered �off budget� meaning the actual cost to run these agencies is not considered by the Office of Management and Budget. By moving the activities of Fannie and Freddie Mac �on budget�, their financial obligations would then be included in the federal government�s budget and debt projections and provide a more accurate picture of our nation's precarious finances.

�The Accurate Accounting of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac Act is a much needed remedy for a Washington that needs to come to terms with their spending addiction. One thing we know about Fannie and Freddie is that they cost the already overburdened and financially strapped taxpayer a pretty penny.

�Why should Fannie and Freddie be able to run up these numbers without the President having to reflect this risk in his budget? It just doesn�t make sense, and we owe it to the taxpayers to be transparent and forthcoming on the commitments we�re making with their credit card.�

Not to mention the fact that Fannie and Freddie are now paying off private debt holders of its MBS that are 120 days or more delinquent. It gets bad debt off the books of the two companies, but investors receiving this money are now getting money they cannot reinvest at the rates they used to get. Realizing the losses on those MBS will add to the cost of the bailout of these two firms -- it's worth remembering that the AIG bailout cost US taxpayers a relatively modest $9 billion.

Chief author of the legislation is Rep. Scott Garrett of New Jersey.

Labels: banking, economics, Michele Bachmann

Price discrimination story of the day

Mandalay Beach offers an 11-acre tropical lagoon which features a sandy beach, three exotic pools and a lazy river. Mandalay Beach's large 1.6 million gallon wave pool can reach waves as high as 6 feet. The lazy river called the Tropical River is perfect for relaxing the day away while floating on your inner tube. For those who like comforts of a classic pool, they have one of those as well."Are you going to Vegas soon, King?" Why yes I am, but I prefer the more old-fashioned hotels. Treat me nicely and I'll send pictures.Moorea Beach Club is separate and secluded area off of Mandalay Beach. Only 21 and older are allowed for entry as the club offers European sunbathing (topless). The Club has a separate pool, along with other perks such as chilled towel service and complementary selection of sun products.

Moorea Beach Club admission prices:

- Monday - Thursday Men $40.00, Women $10.00

- Friday - Sunday Men $50.00, Women $10.00

I'm still working on this "chilled towel service" idea. Is this a perk?

(h/t: Dave Switzer.)

P.S. I'm presenting a paper on sports gambling Thursday there. I have Two for the Money on my iPod -- haven't seen it before. Watched Casino last week. Any other good movie ideas?

Labels: economics

Monday, February 22, 2010

That trick never works

For many, price controls may seem like a tempting solution to holding down health care costs. However, past attempts at price controls teach us a very different lesson�this is one government policy guaranteed to do more harm than good. In fact, throughout history, price controls have been a notorious flop, bringing on economic stagnation and decline, rationing, hoarding, black marketing and organized crime, assaults on civil liberties, and even inflation, not to mention untold waste, graft, and human suffering.Thus wrote Simon Rottenberg and David Theroux in 1994 when we last debated price controls in health care. Some of the stories they tell come from overseas with regards to health care:

In fact, from Babylon�s King Hammurabi to presidents Richard Nixon and Jimmy Carter, the thirty-eight-century history of price controls is a recurring economics lesson for any modern Luddite seeking a quick fix to health care costs. For instance, after he and previous emperors had debased the currency, creating rampant inflation, the Roman emperor Diocletian set maximum prices on more than one thousand products and services. Goods disappeared in legal markets, and reluctantly consumers and producers turned toward black markets despite a penalty of death for participating in these markets. After much suffering and bloodletting of the unfortunate caught violating the law, the law was revoked and Diocletian abdicated.

- price controls on drugs in Germany in 1993 led to one in five firms cutting hours for their workers within a year, and 30-50% of firms experiencing sharp declines in drugs ordered. Families were upset about the unwillingness of doctors to prescribe medicines they requested;

- U.S. doctors were routinely advertising in Canadian newspapers, offering services that were cheaper in Canada ... but unavailable.

The Obama Administration's proposal leads to rationing of health insurance (or as Arnold Kling calls it, health insulation) that probably will not be on a queuing system. It creates a shortage, as any effective price control does. To provide the health insurance to others you will have government subsidies paid for by additional taxes. The growth-damaging effects of those additional taxes will not be recognized.

And as prices are reduced and people continue to be promised health care at near-zero marginal cost, insurance companies will slowly suffocate. Who will save us?

Labels: economics, health care, Obama

Credit cards -- cui bono? cui pendo?

Other rules will make it harder for others to get credit. Some of them just make sense: You need to be notified if your interest rate is going up with enough time to change cards if you don't like it. Your initial rate is frozen for a year. 21 days between getting your bill and having it due. This may reduce credit availability unless banks make their money elsewhere. And they are. James Kwak tells us this is all about shifting the burden of consumer credit from consumers -- who, you know, actually get the credit and decide when to pay off their debts -- to the retailers who sell stuff on credit.

...this is the credit card industry (partially) shifting its sights from consumers, who benefit from (modest) legislative and regulatory protections, to the retailers, who don�t. It�s also what you would expect when you have extremely high concentration among card issuers (and transaction networks) and low concentration among retailers. Perhaps consumers aren�t the only constituency that needs a little protection.Might be a good time to remind you it's America Saves Week. Except in Washington, St. Paul, or a state capitol near you.

(Been a long time since I tried some Latin in a subject. Probably a bit rusty on my translation.)

Labels: economics

Thursday, February 18, 2010

Life at the top

To make the top 400, a taxpayer had to have income of more than $138.8 million. As a group, the top 400 reported $137.9 billion in income, and paid $22.9 billion in federal income taxes.The report details sources of deductions as well as of income. Over half of deductions came from charitable contributions, which totaled $11.1 billion. No wonder the Obama Administration wishes to limit that deduction! The group also paid $5.4 billion in state and local taxes and $1.6 billion in taxes to foreign countries.

About 81.3% of the income of the top 400 households came in the form of capital gains, dividends or interest, the IRS data show. Only 6.5% came in the form of salaries and wages.

Over the past 16 tax years 3,472 different taxpayers showed up in the top 400 at least once. Of these taxpayers, a little

more than 27% appear more than once. In any given year, about 40% percent of the top-400 returns were filed by taxpayers who weren�t in that exclusive club in any of the 15 years .

But the last paragraph is what interested me most. 73% of taxpayers who made the top 400 only made it for one year. 7 taxpayers made it all 16 years. The top 400 "mostly represent a changing group of taxpayers over time, rather than a fixed group of taxpayers." When people want to talk about "the uber-rich" they describe a fleeting thing.

Labels: economics

Encouraging profligacy

The $400/$800 Making Work Pay tax credit took effect in July 2009. Workers who have taxes withheld from their paychecks will see a decrease in the federal income taxes withheld from each paycheck by about $30 per paycheck every two weeks or $60 for couples.We are encouraging younger people to spend rather than save. And perhaps how this works is by giving the money back in $30 dribs and drabs that they don't notice. Wasn't this how we got into trouble in the first place? Why does government think it should encourage consuming new goods rather than paying off debt?

...The credit will phase out by two percent of any income over $150,000 for couples and $75,000 for others. Couples earning more than $190,000 and individuals earning more than $95,000 will not benefit from the credit.Unlike the 2008 economic stimulus tax rebate checks that were mailed to taxpayers in a lump sum, the government is hoping that offering the $400 Make Work Pay tax credit as a reduction in payroll deductions will encourage taxpayers to spend the credit rather than save the money or use it to pay down debt.

Karl noted a few weeks ago that the government is ending this credit as well, since it was expected to spend $116.2 billion over ten years, quite an expensive program. Perhaps one reason for cutting it was that voters like my son didn't even know they were getting it. When I told my son how he had gotten this credit already, all I got was the cryptic 'K'.

Labels: economics, Obama, taxes

Like you couldn't see this one coming

A key software system for the 2010 Census is behind schedule and full of defects, and it will have to be scaled back to ensure an accurate count of the U.S. population, according to a government watchdog report.At least it's not the software that does the actual counting. Again I wonder -- why can't you privatize the Census? There are many firms that will sell you software for scheduling and paying workers.

Even as Census takers have begun the decennial head count in Alaska and other remote areas, the system is still not ready to handle the paperwork and payroll data for what eventually will be a half-million Census takers.

The software to schedule, deploy and pay Census takers is at risk, according to the report released this week by the inspector general for the Commerce Department, which includes the Census Bureau. If changes are not made, the Census risks ballooning costs, delays and inaccuracies.

Labels: economics

Wednesday, February 17, 2010

What we don't know

Most of what we write about the effects of stimulus are just that, "an attempt to gain knowledge." A bureaucrat writes down some numbers. Reporters and bloggers find flaws. Econometric models estimate the effects, but those models were used to propose the policy put in place. It's not likely those models would go back and say the proposed plan didn't work: Econometric models aren't built to do that: If the model has as a premise that future government spending will create jobs, it isn't going to tell you that past government spending did not. Meanwhile, those in political opposition will look to find contradictions when none really exist. (GDP growth can lead employment growth.) And people get angrier and cynical.Most of what Thomas Friedman thinks we know is based on multiple regression analysis trying to hold other factors constant other than human carbon emissions and making a variety of assumptions about the interactions between those factors along with the factors we cannot measure. That is hard to explain to a sixth grader. It can be done But it�s not knowledge. It�s an attempt to gain knowledge.

It is very similar to writing a report for a sixth grader on how the stimulus turned out. We have fewer jobs than we had before. That�s what we know. But even I, a skeptic, wouldn�t call that knowledge about whether the �stimulus� package worked or not. But I wouldn�t use the CBO estimate either. The CBO estimate is a repeat of the forecast it made before the legislation passed. We don�t know how many jobs were created or destroyed by the legislation.

There is nothing wrong with saying we don't know. It might have worked; it might not have. What we know is there are between three and four million fewer jobs than a year ago, and the deficit is larger. We want to know more. We are trying to know more. And if the volume of studies since 2000 of the Great Depression are any indication, we'll still want to know more a century from now.

Labels: economics

The Georgian example

The aristocrats of the Caucasus recently adopted something called the Liberty Act, which limits their deficit to 3 per cent of GDP and their public debt to 60 per cent. The proportion of economic activity generated by the state is capped by law at 30 per cent, and the number of government licences and permits is likewise restricted. At the same time, control of public services, including healthcare and education, is shifted from state to citizen.Using the shortcut measure of economic freedom from the Heritage Foundation, Georgia does very well compared to its peers, though Heritage reports government spending as a share of GDP at 34% rather than 30. It ranks ahead of Vaclav Klaus' Czech Republic on that scale and 26th in the world.

Result? Georgia�s GDP is flourishing despite the Russian embargo and the recent war, and the country has continued to grow through the downturn.

Tuesday, February 16, 2010

An evening thought about prices

One element of stimulus that I think might not work as planned is infrastructure investment. Let�s look at the I-35 bridge that collapsed in Minneapolis and was rebuilt in 2007-8. According to Wikipedia, the original bridge cost $5.2 million to build in 1964-7, which is roughly $35 million in today�s dollars (admittedly not a bargain, given that it collapsed, but the collapse was due to a design flaw, not faulty construction or shoddy materials). The replacement cost $234 million. Public infrastructure, employing as it does an army of civil servants (and their pension obligations), union labor, and drawers full of lawyers, turns out to be one of the most expensive things in the world to buy. A sensible consumer, faced with an 7X increase in the real price of a good, would purchase less of that good rather than more.Philip Greenspun. Recall, of course, that we probably didn't go for the lowest cost on the replacement of that bridge -- we were in a hurry to get back a key artery of a major metropolitan area and speed was considered as a tradeoff to cost. And the 2008 bridge is not a replacement for the 1967 bridge -- you can't build that bridge any more, the design no longer is used by anyone (and considered unsafe.)

All that said, is it possibly true that the real price of government goods has risen? A bonding bill cannot pass without a provision that assures wages will be higher. A labor union claims the bill provides 21,000 jobs without asking "if that amount of money was spent by a private firm building its own infrastructure, how many jobs would that provide?" And for how long would those jobs last?

Government is not "a sensible consumer." In fact, thinking about a price of real government services, can we actually conceive of its demand curve?

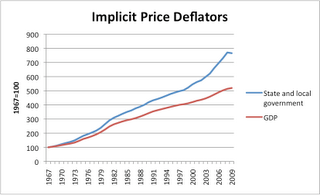

UPDATE: In comments Speed Gibson got me wondering about the implicit price deflators for state government spending, so I drafted a very quick graphic.

There are many ways to criticize a deflator, and many criticize them. But it's hard to find a better measure. I don't think they just take the deflator for all goods and add 1%, as SG suggests. It's late, someone else may find a better answer in the morning.

Labels: economics, it's the spending stupid

Worth your time

This is not a new story, at least not to me. I co-authored a paper published in 1994 with Hal McClure and Tom Willett in which we argued that the optimal inflation rate was probably zero for most economies if there was a tradeoff of even 1% of GDP growth for a 10% anticipated inflation rate. Developing countries are usually assumed to have a smaller tradeoff. There are non-linearities or threshold effects involved as well. (I don't know of a summary paper that covers the literature and none were obvious from looking on Google Scholar, at least not since Bruno and Easterly [1998]. If anyone knows one, please put in comments.)To be sure, there are plenty of studies suggesting modest increases in the rate of inflation from the levels currently targeted by many central banks would not be problematic�here, for example. But the point is that the evidence is not clear cut that an increase from an average rate of inflation in the neighborhood of 2 percent to the neighborhood of 4 percent would be innocuous. And there is always this element, noted by John Taylor in the aforementioned Wall Street Journal article:

"John Taylor, a Stanford University monetary-policy specialist who served in the Bush administration Treasury department, says that inflation could become hard to constrain if the target is raised. 'If you say it's 4%, why not 5% or 6%?' Mr. Taylor said. 'There's something that people understand about zero inflation.' "

Arguing for higher inflation targets at a time like this is a call for cheap credit, which seems like trying to do the same thing we did in 2004-05 while hoping for a different outcome.

Labels: economics

Which spending limitation amendment?

... we are offering a proposal in the current legislative session to let you vote on a constitutional amendment that would restrain state spending to the amount of money actually collected during the previous budget. Apply this concept to your own situation: If you make $40,000 this year, you don't set a larger budget for next year based on the possibility that you will make more money. You certainly can't storm into your boss's office during a recession and demand a 20 percent raise to meet your lofty spending visions. But that is exactly what government does. It sets a budget based on what it hopes to have, and comes calling for more of your money if that hope turns out to be wrong.Which sounds lovely as far as it goes, but what follows next is troublesome.

Our amendment would inject reality back into the budget process. But unlike attempts in other states, we would not be backing ourselves into a corner. On the occasion that government should take in more than it spends, the money would be used to build up rainy day funds, given back to taxpayers or spent on meeting a one-time need, like repairing a bridge or a building. That would be the case under the most recent budget forecast, which shows future revenue exceeding current spending by nearly $2 billion. The key is the Legislature would maintain the flexibility to use the surplus for one-time expenditures as it sees fit. The last time the budget had a surplus, in 2007, the money went primarily to support on-going spending that we can no longer afford. Had it been spent on one-time construction or maintenance costs, our spending problem would be less severe and our infrastructure much improved.The government currently budgets for repairs and maintenance. It takes nothing to shift spending so that all of those maintenance expenditures show up in extra monies in one year and then put into continuing expenditures in subsequent years. I can also imagine DFLers complaining that maintenance of our bridges and roads depends on the state of the economy.

Giving any legislative body flexibility is unwise, as the history of government spending has chosen. As I wrote last time, this formula assures higher spending when times are good, and a reason to hold huge reserves to prevent any cut in government's role in the economy when recessions force a re-evaluation. When I asked gubernatorial candidate Marty Seifert about this amendment he indicated he thought it would encourage more spending in boom times than wise. A $5 billion deficit for a future biennium focuses the mind of the Legislature and the next Governor to think about what is sustainable. Why not keep the legislature constantly focused on that sustainable level?

On Rod Grams' radio show this morning we talked about this very issue. I suggested there that the only way to hold the government to a spending limit is to give them a real limit, established beyond their control and without wiggle room. There are models around us right now: Kansas has a proposal before its legislature to restrict growth of spending to inflation only. Other variations are out there. A population-and-inflation limit provides a slow steady increase while holding the real cost of government per capita constant. If government can make itself more efficient it can generate new public goods. Any funds obtained in excess of that limit can be placed in the rainy day fund or returned to taxpayers only. There's ample lesson from California's Prop. 4 to tell us what happens when you let the legislature and governor game that system for spending on designated areas. So don't.

Monday, February 15, 2010

Similar to 1981?

I like this passage. But what I found in MM's description was this:

When Ronald Reagan took office on January 20, 1981, our nation was facing a terrible economic crisis, similar to what we are experiencing today. This video contains excerpts of Reagan's first inaugural address. His prescription to solve the economic crisis was vastly different than the policies being pursued by the Obama administration.Emphasis mine. But the speech describes a far different world than the one Obama is in. Reagan said:

These United States are confronted with an economic affliction of great proportions. We suffer from the longest and one of the worst sustained inflations in our national history. It distorts our economic decisions, penalizes thrift, and crushes the struggling young and the fixed-income elderly alike. It threatens to shatter the lives of millions of our people. Idle industries have cast workers into unemployment, human misery and personal indignity.Who among us would think that story is similar to today? Inflation has not been an issue this past decade -- if anything, we faced deflationary pressures in the recession and may yet face more. Tax rates in 1980, particularly on high-income earners, were much higher than they are now -- in fact, twice as high at the top end. Productivity growth was substantially higher in the late 1980s and 1990s than in the 1970s, and so far has accelerated through this recession.

Those who do work are denied a fair return for their labor by a tax system which penalizes successful achievement and keeps us from maintaining full productivity. But great as our tax burden is, it has not kept pace with public spending. For decades we have piled deficit upon deficit, mortgaging our future and our children�s future for the temporary convenience of the present. To continue this long trend is to guarantee tremendous social, cultural, political, and economic upheavals.

You and I, as individuals, can, by borrowing, live beyond our means, but for only a limited period of time. Why then should we think that collectively, as a nation, we are not bound by that same limitation?

I certainly have said enough to readers to understand that I think Obama fiscal policy has made several missteps. But a simple hearkening to the days of the Gipper is a poor substitute to thinking through new policies.

This isn't new. We have people constantly holding up conservatives against the Reagan yardstick and finding out nobody measures up. The recent kicking of Paul Ryan is but one example. But none of them would know what Reagan would have said about this current situation or how he would have voted. Rep. Ryan has explained his votes; you can draw your own conclusions, but suffice to say purity is a rare thing.

As are parallels between 1981 and 2008-09.

Labels: economics, Reagan, Republicans

History may repeat

In this paper we provide some evidence on when central banks have shifted from expansionary to contractionary monetary policy after a recession has ended--the exit strategy. We examine the relationship between the timing of changes in several instruments of monetary policy and the timing of changes of selected real macro aggregates and price level (inflation) variables across U.S. business cycles from 1920-2007. We find, based on historical narratives, descriptive evidence and econometric analysis, that in the 1920s and the 1950s the Fed would generally tighten when the price level turned up. By contrast, since 1960 the Fed has generally tightened when unemployment peaked and this tightening often occurred after inflation began to rise. The Fed is often too late to prevent inflation.Michael Bordo and John Landon-Lane, in a new NBER working paper (ungated copy here.) Since September 23rd's FOMC statement the Fed has been emphasizing "resource utilization" and "resource slack", code for unemployment. Will prices turn north again before the Fed starts this new policy?

Labels: economics, Federal Reserve, money

What do we mean by sustainable debt?

From 2005 to 2007, before the recession and financial crisis, the federal government ran budget deficits, but they averaged less than 2 percent of gross domestic product. Because this borrowing was moderate in magnitude and the economy was growing at about its normal rate, the federal debt held by the public fell from 36.8 percent of gross domestic product at the end of the 2004 fiscal year to 36.2 percent three years later.And that's using the more favorable growth and spending assumptions in the Administration's budget. If you use CBO, the story gets worse. This is why the figures Menzie Chinn shows only take us so far: One can easily imagine a case where cyclical adjustment in a recession causes a temporary rise in the debt-to-GDP ratio without a concern about sustainability, if in the long run we stabilize and eventually reduce that ratio.

That is, despite substantial wartime spending during this period, budget deficits were small enough to keep the debt-to-G.D.P. ratio under control.

The troubling feature of Mr. Obama�s budget is that it fails to return the federal government to manageable budget deficits, even as the wars wind down and the economy recovers from the recession. According to the administration�s own numbers, the budget deficit under the president�s proposed policies will never fall below 3.6 percent of G.D.P. By 2020, the end of the planning horizon, it will be 4.2 percent and rising.

As a result, the government�s debts will grow faster than the economy. The administration projects that the debt-to-G.D.P. ratio will rise in each of the next 10 years. By 2020, the government�s debts will equal 77.2 percent of G.D.P.

Debt market participants are forward looking. What they concern themselves with is that the debt they are buying are not part of a Ponzi scheme. To make a long story short (the long, mathematical story is here if you're curious), your country must be expected to run budget surpluses some time in the future to pay off the current debt. There's discounting involved of course, but most important is the difference between your country's real interest rate and the rate of growth of real GDP. (One of the remarkable lessons of the theory is that you can't inflate your way out of the problem, as long as we assume nominal interest rates fully adjust to higher money growth rates being used to pay off the debt. Read around the math of that last link for more.)

What matters most then are either policies that bring down the primary deficit, those that maintain our credit such that real interest rates are reduced, and those that increase the growth rate of GDP. At present the primary deficit -- the deficit less interest payments on the debt -- doesn't stabilize. It's not necessarily the bomb that Ed is talking about; this debt is a very slow rotting of the nation's economic health, taking a couple of decades to become apparent. It's worth remembering in this story that while the government may show you the debt "held by the public", the bonds in the trust funds are being held in trust for the public. Interest on those bonds in the trust funds are meant to pay for future benefits for Social Security, Medicare, railroad pensions, etc. At present all we have is the past good credit of the US and a promise by the Obama Administration to get serious ... by forming a committee to tell us how to get serious.

Labels: economics

Friday, February 12, 2010

Stenting competition

Actually, it's already happening. Announced earlier in the week, the company is cutting 1,300 jobs, with many likely to come from the Twin Cities.

Boston Scientific has been facing a lot of headwinds lately. They recently had to make a $1.7 billion payment to their competitor Johnson and Johnson over patent disputes and sales of key products are down. They include drug-coated stents, mesh tubes that prop open clogged arteries, and cardiac rhythm devices, which treat irregularly beating hearts.It's not a great example for Malkin's narrow point about the company and stents, but in the broader sense it makes a very good point. These companies that produce valuable, life-extending medical devices -- just ask President Clinton, or my dad who has a few of those in him -- live in a profit-and-loss system, one that is quite competitive. The company does not run on a very large profit margin with competition from places like JNJ and Medtronics and St. Jude Medical, etc. To the extent that government regulation damages these firms we could see a loss of competition and higher prices for devices, leading to government price controls and non-price rationing. Not that ex-Presidents will ever go wanting for a stent, but for you and me that's not a pleasant prospect.

CEO Ray Eliot joined the company last summer and said during a conference call Thursday that investors should be patient with his efforts to improve the company's results.

"This is a big ship," Eliot said. "I don't care how smart you are, you don't turn this around in a quarter or two, and it...has had some underlying issues that I think we've addressed well. "

Media alert

Thursday, February 11, 2010

Bye-bye Fed funds target

The text is here. In it Bernanke also suggests a new instrument for removing excess reserves from the system, a term deposit banks could make to the Fed that would compete with Treasuries as a store of liquidity for them.�Although at present the U.S. economy continues to require the support of highly accommodative monetary policies, at some point the Federal Reserve will need to tighten financial conditions by raising short-term interest rates and reducing the quantity of bank reserves outstanding,� he wrote.

�We have spent considerable effort in developing the tools we will need to remove policy accommodation, and we are fully confident that at the appropriate time we will be able to do so effectively.�

Mr. Bernanke, however, did provide new details of a major concern: how, as the recovery proceeds, to gradually shrink the balance sheet, which along with a vast array of assets also includes $1.1 trillion that banks are holding with the Fed.

Mr. Bernanke suggested that a new policy tool � the interest rate on excess reserves, which the Fed began paying in October 2008 � would be a vital part of the Fed�s strategy.

Increasing that interest rate, he said, will have the effect of pushing up other short-term interest rates, including the benchmark fed funds rate � the rate at which banks lend to each other overnight.

The Federal Reserve would likely auction large blocks of such deposits, thus converting a portion of depository institutions' reserve balances into deposits that could not be used to meet their very short-term liquidity needs and could not be counted as reserves. A proposal describing a term deposit facility was recently published in the Federal Register, and we are currently analyzing the public comments that have been received. ... we expect to be able to conduct test transactions this spring and to have the facility available if necessary shortly thereafter. Reverse repos and the deposit facility would together allow the Federal Reserve to drain hundreds of billions of dollars of reserves from the banking system quite quickly, should it choose to do so.Both new instruments provide a means by which the Fed can increase its balance sheet without impacting the money supply, by inducing banks not to use their excess reserves for deposit expansion. I was familiar with both these instruments in Macedonia, where excess reserves were close to 30% of the money supply. The problem there was that it created flabby banks unwilling to lend, since easy government revenue was close at hand. The Fed does not directly spend taxpayer dollars, but its remission of excess earnings from its portfolio to the Treasury would be shifted to banks, and that indirectly expands the government's need for additional debt to cover its spending. That's not likely to go over well.

The biggest signal was not a date but a statement that the Federal funds rate would no longer be a policy instrument for the Fed, at least for awhile:

As a result of the very large volume of reserves in the banking system, the level of activity and liquidity in the federal funds market has declined considerably, raising the possibility that the federal funds rate could for a time become a less reliable indicator than usual of conditions in short-term money markets. Accordingly, the Federal Reserve is considering the utility, during the transition to a more normal policy configuration, of communicating the stance of policy in terms of another operating target, such as an alternative short-term interest rate. In particular, it is possible that the Federal Reserve could for a time use the interest rate paid on reserves, in combination with targets for reserve quantities, as a guide to its policy stance, while simultaneously monitoring a range of market rates. No decision has been made on this issue; we will be guided in part by the evolution of the federal funds market as policy accommodation is withdrawn. The Federal Reserve anticipates that it will eventually return to an operating framework with much lower reserve balances than at present and with the federal funds rate as the operating target for policy.The last time the Fed abandoned the Fed funds target was October 1979, when then-Chair Paul Volcker thought it more prudent to stop inflation by using a target on reserves. That lasted perhaps three years, maybe less (see Alton Gilbert for more.) That period led to rather high volatility in interest rates may have contributed to the double-dip recessions in 1980-82.

It would be fair criticism of the above to say we really haven't used the Fed funds target for awhile and that this is just recognition of reality. But the FOMC statement still focused on it, and the Fed had not enunciated until yesterday what we might look at for an alternative target. Now we have. This will make reading the next FOMC statement on March 16 very interesting indeed.

UPDATE: John Taylor doesn't like the term deposits from the Fed to the banks.

In my view, Fed borrowing instruments should be avoided as much as possible because they delay essential adjustments in reserves and create precedents which make it easier to deviate from the monetary framework in the future. Similarly, the instrument of paying interest on reserves to achieve the short term interest rate target should be used only during a well defined transition period.He argues instead for a rule that ties Fed fund rate increases to a decrease in reserves. It would make Fed policy more predictable.

[P]olicy makers could treat this exit rule as an exit guideline rather than a mechanical formula to be followed literally, much as a policy rule for the interest rate is treated as a guideline rather than mechanical formula. They would vote on how much to reduce reserves at each meeting along with the interest rate vote. Note that the exit rule would we working in tandem with a policy rule for the interest rate, such as the Taylor rule.With all that's going on in Europe, this might be sliding under the radar. It shouldn't.

Labels: economics, Federal Reserve, money

Rose bowls at the margin

...there are two costs that seem especially relevant: (1) The costs of getting big donations are more than just seats on a plane to the Rose Bowl. Tremendous amounts of time, energy, and resources go into "asks," and these costs should be factored into the whole calculation about whether a firm/university is "making it." (2) Universities like UW-Madison receive a tremendous amount of support from taxpayers. Thanks to taxpayer subsidies, prices for tuition are kept artificially low. Furthermore, many student scholarships are funded by tax dollars. (Here, in Georgia, for example, lottery revenues cover tuition costs for all students with a B or better average in high school.) Again, these are just two of the relevant costs that must now be considered once we take the "look at the overall picture" approach.This is no doubt true, but one would want to think then about the rate of substitution between the salary of another fundraiser in the alumni office and the recruiting costs of a star quarterback. Given that the athlete is barred from receiving a wage, it may be that the relative prices of athletes and fundraisers tilts towards a better athletic program and fewer glad-handers.

There are also questions to be raised about whether your basketball team getting to the Final Four of the big dance gets you more applications for admissions, from people with parents with deep pockets perhaps. It's advertising for your school, which is much cheaper in basketball than football due to team size (and why so many schools want D-I basketball programs.) Prof. Beaulier is right, you can add more costs on if you want ... and more revenues. This is why economists like that ceteris paribus assumption.

So maybe we take Prof. Beaulier's Austrian advice and say "we just don't know," which is true if you insist on moral certitude as your standard of knowing. Or we could think marginally, arguing that for the last person you put on the plane to the Rose Bowl, the price of the ticket was lowered to induce an additional contribution to the alumni fund, given the fixed costs of the alumni office's payroll. I wouldn't call that a moral certitude, but I can predict a great deal of human behavior thinking marginally.

Tax migration and context

But meanwhile, in a new study released yesterday by the Freedom Foundation of Minnesota, two researchers looked at the IRS' data on income tax filings and returned a strong conclusion:

From 2002-2009 Minnesota lost an estimated 54,113 residents to other states, according to the new report, Minnesota�s Out-Migration Compounds State Budget Woes. These out-migrants also take their incomes with them. Between 1995 and 2007, the total amount of income leaving the state was at least $3,698,692,000 on which state and local governments would have collected an estimated $423,317,000 in additional taxes.For example, in 2007 -- the last year of their study, a net 4,428 taxpaying units left the state, and took $378,757,000 in AGI with them. By aggregating up the thirteen years of study they find that a total of $2.548 billion in additional taxes would have been collected. That's of course over 13 years, a period in which we would spend maybe 80 times that? I would have liked that number put in context, just as the income data should be put in context of state personal income ($216,436,888,000 in 2007, to put it in the same context the FFM study does.)

What caught my eye as well was their ability to identify where the taxpayers moved to. The top five destinations of out-migrants were Arizona, Florida, Colorado, California and Texas. Four of those places are very warm. We talk about the low taxes of South Dakota, though on net 1,322 taxpaying units moved TO Minnesota. But on net more AGI left than came. What was missing here was an attempt to tease out the effects of other factors they identified like weather or cost of housing. The study shows these factors as important, but doesn't get relative importance of these additional factors. That requires a regression analysis, which that study chose not to do.

But this is a very interesting and worthy study. It uses actual tax return data rather than a survey or the loose proxy of moving vans. It can measure income flows separately from people flows. And it fits the theory that people are sensitive to the cost of government.

Labels: economics, Minnesota, taxes

Eurohandcuffs

Germany and France will on Thursday promise their support for debt-laden Greece in a vow of eurozone solidarity but they are unlikely to come up with a detailed rescue plan.At the time this is posted, we have only word that they have an agreement to take "co-ordinated measures""if needed to safeguard stability of the euro zone as a whole", but no details.

President Nicolas Sarkozy and Chancellor Angela Merkel are expected to give a show of political support to Athens at a summit of EU leaders in Brussels, one of the most momentous in the bloc�s recent history, in the hope that it will calm debt market turmoil.

But officials in Paris said there was �reticence� in Berlin about signing up to a bail-out package with further �assurances that the Greek government would undertake the measures necessary� to cut its budget deficit by 4 percentage points a year by 2012.

If this was a developing country, there'd be no doubt what would happen -- Greece would be given IMF assistance in return for a plan from the Greek government to restrain government spending -- but this is the Eurozone, and you cannot really do that. And finding a lender of last resort is much harder. Germany, towards whom everyone is looking, seems more constrained these days. STRATFOR reports:

Most investors assumed that all eurozone economies had the blessing � and if need be, the pocketbook � of the Bundesrepublik. It isn�t difficult to see why. Germany had written large checks for Europe repeatedly in recent memory, including directly intervening in currency markets to prop up its neighbors� currencies before the euro�s adoption ended the need to coordinate exchange rates. Moreover, an economic union without Germany at its core would have been a pointless exercise.And that really is the issue: The French and German governments now face the constraints of Maastricht and the ECB charter, which were written to prevent one of those PIIGS from profligacy but never were meant to handle a systemic shock hitting all five at once. A guarantee or pledge of unity for Greece will mean a pledge to all. And the problem then is whether speculators will test the pledge. If they use actual funds they will cause a constitutional crisis in the EU; if they do not, they risk having these countries make an exit from the Eurozone, something nobody is prepared for (even the biggest skeptics.)

...The 2008-2009 global recession tightened credit and made investors much more sensitive to national macroeconomic indicators, first in emerging markets of Europe and then in the eurozone. Some investors decided actually to read the EU treaty, where they learned that there is in fact no German bailout at the end of the rainbow, and that Article 104 of the Maastricht Treaty (and Article 21 of the Statute establishing the European Central Bank) actually forbids one explicitly. They further discovered that Greece now boasts a budget deficit and national debt that compares unfavorably with other defaulted states of the past such as Argentina.

...As the EU�s largest economy and main architect of the European Central Bank, Germany is where the proverbial buck stops. Germany has a choice to make.

The first option, letting the chips fall where they may, must be tempting to Berlin. After being treated as Europe�s slush fund for 60 years, the Germans must be itching simply to let Greece and others fail. Should the markets truly believe that Germany is not going to ride to the rescue, the spread on Greek debt would expand massively. Remember that despite all the problems in recent weeks, Greek debt currently trades at a spread that is only one-eighth the gap of what it was pre-Maastricht � meaning there is a lot of room for things to get worse. With Greece now facing a budget deficit of at least 9.1 percent in 2010 � and given Greek proclivity to fudge statistics the real figure is probably much worse � any sharp increase in debt servicing costs could push Athens over the brink.

From the perspective of German finances, letting Greece fail would be the financially prudent thing to do. The shock of a Greek default undoubtedly would motivate other European states to get their acts together, budget for steeper borrowing costs and ultimately take their futures into their own hands. But Greece would not be the only default. The rest of Club Med is not all that far behind Greece, and budget deficits have exploded across the European Union.

Megan McArdle says it's a design flaw, and she's right to say "none of the choices are good." The markets have so far seemed to put considerable weight on the likelihood of a bailout -- the scene to the left from Athens indicates that a government austerity plan, if enacted, would be very unpopular. Large cash infusions may be the only way to get the public to swallow the bitter medicine. But markets do not seem aware of the constitutional restrictions placed on a bailout package from EU member states or from the IMF.

Megan McArdle says it's a design flaw, and she's right to say "none of the choices are good." The markets have so far seemed to put considerable weight on the likelihood of a bailout -- the scene to the left from Athens indicates that a government austerity plan, if enacted, would be very unpopular. Large cash infusions may be the only way to get the public to swallow the bitter medicine. But markets do not seem aware of the constitutional restrictions placed on a bailout package from EU member states or from the IMF.Thus it is unsurprising that there will be little more than a statement today from the EU members, with details to be worked out later. But time is of the essence, for as we learned in 2008, when the end comes it can be swift and a less-than-united front could cause far greater harm in Europe than what happened here.

UPDATE: Welcome HotAir and Atlanticist readers. Just as a coda to this story, the markets didn't buy the band-aid the EU tried to apply to the gash in the Greek budget:

An attempt by Europe�s richest countries to end the crisis engulfing the euro failed to impress financial markets today as the single currency fell despite promises that the battered Greek economy would not be allowed to implode.The euro is down to about $1.36 as I type this (1:30 pm CT.)

As the EU�s main paymaster, Angela Merkel refused to tie Germany down to a bailout of Athens at a one-day European summit, with EU leaders instead making a general pledge to take �determined and co-ordinated action if needed� to prop up the euro.

The statement of political intent followed a failure by the 16 nations in the eurozone to agree the precise details of a rescue plan for Greece, leaving the euro to lose most of the gains it had made in the run-up to the Brussels meeting of the 27 EU leaders.

I detoured today to talk about U.S. monetary policy but will get back to Greece this PM. Thanks for stopping by.

Labels: economics

Wednesday, February 10, 2010

"Stop stimulating us!"

Washington still does not get it. It pays lip service to the fact that small business generates half of private sector GDP and creates over two-thirds of private sector net new jobs, but when it comes time to provide help, small business gets $30 billion IF banks decide to accept the TARP funds to support loans and IF the owners can subsequently get a loan from a bank. But for most firms, this dinky amount is of little help. More so, this new aid misses the main problem since only five percent of small business owners cite �financing� as their top business problem but 31 percent cite �poor sales.�This from the National Federation of Independent Businesses. Add to it the overhanging burden of health care reform and a minimum wage increase and small business owners are quite nervous ... about getting more stimulus.

The National Bureau of Economic Research is expected to declare a recession bottom in the second half of 2009. Manufacturing turned in the third quarter, employment managed a positive month in the fourth, both determinants of the turning point. The NFIB indicators do not appear to agree however. At the end of the 1982 recession (Q4, 1982), the Index value was 98, the percent of owners viewing that period as a good time to expand was nine percent and the net percent expecting better business conditions was 47 percent. The January Index value is 89.3, the percent of owners viewing the current period as a good time to expand is five percent and only a net one percent expect better business conditions in the first half, not really strong signs of a turn in the economy. The decline in the unemployment rate reflects a reduced number of individuals looking for a job and is more consistent with the NFIB forecast which did not anticipate a continued rise in the unemployment rate above 10 percent. The loss of a lock on 60 Senate votes for the Democrats may be encouraging to some owners, but the President and Congressional leaders still sound like they plan to press on with their agenda, not good news for small business owners.Bruce Yandle does it shorter:

Imagine yourself as owner of a small business with 20 employees. You are trying to decide if you should build up inventories again, hire one or two people, and lease another pickup truck. Would you make your decision on the basis of the fourth quarter GDP numbers? Would you base your plans on the explosion of existing home sales that followed the first-home-buyer stimulus? Most likely not. I�ll bet you would wait so that you could get a better fix on the real economy.When I teach cost-benefit analysis one of the factors we discuss is the value of the option of waiting. Waiting for more information, waiting for a reduction in finance uncertainty, waiting for a reduction in policy uncertainty. Yet we have financial reform hanging up in the Senate -- bipartisanship or ram it through? Policy makers occasionally say they are moving forward with health care, then they want a summit. If you ran a business and I was your silent partner, my silence would be tough to maintain if you started an expansion right now. And there's no sign of a pickup in the hiring rate...

Perhaps we need six months of political silence.

Labels: economics