Monday, November 23, 2009

Deepening production vs ramping up production

If everyone scans the headlines and sees "Great Depression," that could very well cause a drop in consumption. And if everyone scans the headlines and sees "recovery," they might spend more.After a long comparison of information-based businesses versus manufacturing, he concludes:

We could also observe herd behavior among producers. I have been talking a lot about Garett Jones' remark that today's work force produces organizational capital rather than widgets. It is time to elaborate on this notion.

Thus, my experience fits very well with the notion that workers are needed in order to build organizational capital. In today's economy, the organizational capital often is embodied in a computer system of some kind. Those systems depreciate very rapidly, because of technological innovation and the evolution of business demands.The Quarterly Business Report we do at SCSU for central Minnesota includes a survey of local business leaders. We don't take a temperature of business confidence directly, but we can track their assessment of the national economy along with their own plans to expand payroll, wages to be paid and prices to be received, etc. I have long wanted to see if these data could be used somehow in a confidence index. There is some evidence that business confidence is a turning point indicator (McNabb and Taylor [2002], Holmes and Silverstone [2007] ). There's also at least anecdotal evidence that reporting on economic news influences that confidence. (This is why President Obama probably shouldn't say "double dip recession" in public.) Indeed, Google Trends still averages ten times more for recession than economic recovery.

Other forms of organizational capital are embodied in human capital. For example, an airline needs to have an effective program for training its employees and for ensuring the quality of their work. If your flight attendants are surly, some of your customers will switch to a different airline next time.

The macroeconomic significance of all this is that the choice of when to invest in organizational capital is discretionary. If you read a bunch of headlines that say "economic downturn," you can cut back your labor force to just the number of people needed to keep today's business operating. If you read a bunch of headlines that say "recovery," you may become inclined to invest in projects that make your business more complex or more competitive.

Labels: economics, forecasting, St. Cloud

Wednesday, November 04, 2009

Graphs that make you go hmmmm

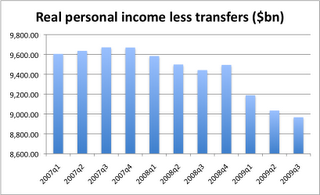

I do a number of local talks in town, usually a couple per month, but for some reason I hadn't done any big ones in the last six weeks. So when I was prepping for this morning's talk to the collected Rotaries of the area, I had to put some new slides together. Whenever I do this, there's one that tells me something I did not realize before. The one above is this months thing-I-didn't-know-before.

I do a number of local talks in town, usually a couple per month, but for some reason I hadn't done any big ones in the last six weeks. So when I was prepping for this morning's talk to the collected Rotaries of the area, I had to put some new slides together. Whenever I do this, there's one that tells me something I did not realize before. The one above is this months thing-I-didn't-know-before. During each of the second and third quarters, the Making Work Pay Credit provision lowered personal taxes and raised disposable personal income about $50 billion (annual rate). During the second quarter, ARRA provided payments of $250 to beneficiaries of social security and other programs that raised disposable personal income about $55 billion. ARRA also provided special government social benefits for unemployment assistance, for student aid, and for nutritional assistance; these special benefits raised disposable income about $49 billion in the third quarter and about $35 billion in the second quarter. ARRA also funded current grants (such as Medicaid) and capital grants (such as highway construction) to state and local governments of about $75 billion in the third quarter and $85 billion in the second quarter.How much of our third quarter GDP growth is due to this stimulus? Maybe more than we think. But how long will it last? Harder question. What I know is that after looking at this graph, I have a harder time finding the trough of the current recession. Both income and employment declining? I know monthly GDP turned positive in July (only 2 months of data so far), and I know there are revisions to the data forthcoming. So I could be wrong, but I need more evidence before I start thinking the national economy reversed.

UPDATE: Looking at James Hamilton, I see he has the monthly disposable personal income graph. But that has all those transfers, like the $250 checks to seniors, included in it and I think that view is distorting the underlying trend. Look at page 6 of the monthly income and consmption data report (published last Friday.) I'm looking at the line labeled "Personal income excluding current transfer receipts, billions of chained (2005) dollars" -- it's the last boldfaced line at the bottom of that page. That pulls out the effects of the stimulus. If the economy was getting better, wouldn't that number be rising? Or am I just asking for too much?

Labels: economics, forecasting

Thursday, October 15, 2009

Forecasting luxuries I can't afford

Like Scott Beaulier, I have been asked whether the latest NABE survey that 80% of its respondents think the recession is over is true. And like Beaulier, my first answer is that "it's a survey" which is asking in effect the question "when the NBER business cycle dating committee dates the trough of the Great Recession, what date do you think they'll put on it." Since the survey was done in September, the respondents are saying "we think they'll set it sometime in July or August" (I doubt anyone would say it ended in the second quarter.) We looked at that data last week and you'll know I concluded that "we need a certain move in GDP AND in employment" before we should put a date on it. So I'm in the 20% on that one, but maybe I'm just a lagging indicator :) As I noted, the second derivative issue (or, if you will, the inflection point issue) is a real problem for any forecaster, as Beaulier acknowledges in his third point. We agree there.

What I would resist, however, is some of the lampooning of forecasters that Beaulier engages in:

...many of the "economists" they're surveying are business economists applying flawed forecasting models. Generally speaking, they are not academic economists, who have a stronger sense of unintended consequences and theoretical nuance.And

I view this kind of economics as hackonomics at its worst, and I don't put much stock in the predictions they make.The job of a forecaster is to forecast, to try to get the next number right. Whether I have a "stronger sense of unintended consequences and theoretical nuance" is useful insofar as I get closer to the right number. Beyond that it's only for smug faculty club conversation. I live in a fairly small city; my life gets spent in both the academic world and in Central Minnesota's business community. (I'm not the only forecaster who works in academia, of course.) I educate while I forecast and some "theoretical nuance" hopefully comes out of that. But because I also meet and sometimes share panels with "business economists", I have a view of them that would consider this "hackonomics" smear to just that. It's damn unbecoming.

If the horseshoe works, I use it. I'd like a model that predicted better that didn't use the horseshoe. It'd be swell; I could be confident in both the faculty lounge and the rubber chicken business luncheons I speak at. But there is no tradeoff between theoretical purity and forecast accuracy. Whatever it takes to get an accurate forecast, I'll use.

(BTW, I don't make national forecasts, at least not publicly. I did it as a training exercise for graduate students when I taught forecasting for them. But I retired that model and turned that class over to my younger colleagues a few years ago. So I don't participate any more in any of the national surveys. I don't use any national indicators in forecasting St. Cloud. And I don't have the luxury of "following the herd" because there is no herd forecasting Central MN.)

Labels: economics, forecasting

Wednesday, August 12, 2009

Don't get too excited

Information received since the Federal Open Market Committee met in June suggests that economic activity is leveling out. Conditions in financial markets have improved further in recent weeks. Household spending has continued to show signs of stabilizing but remains constrained by ongoing job losses, sluggish income growth, lower housing wealth, and tight credit. Businesses are still cutting back on fixed investment and staffing but are making progress in bringing inventory stocks into better alignment with sales. Although economic activity is likely to remain weak for a time, the Committee continues to anticipate that policy actions to stabilize financial markets and institutions, fiscal and monetary stimulus, and market forces will contribute to a gradual resumption of sustainable economic growth in a context of price stability.It's that last line that will create a buzz more than the "leveling out", as it's an indication that the period of quantitative easing may have reached its apex. But let's remember all the steps they've taken. The New York Times points to the $1.25 trillion purchase of mortgage-backed securities as evidence this hasn't come to an end yet. It still is running $100 billion auctions on a regular basis.

...The Committee will maintain the target range for the federal funds rate at 0 to 1/4 percent and continues to anticipate that economic conditions are likely to warrant exceptionally low levels of the federal funds rate for an extended period. As previously announced, to provide support to mortgage lending and housing markets and to improve overall conditions in private credit markets, the Federal Reserve will purchase a total of up to $1.25 trillion of agency mortgage-backed securities and up to $200 billion of agency debt by the end of the year. In addition, the Federal Reserve is in the process of buying $300 billion of Treasury securities. To promote a smooth transition in markets as these purchases of Treasury securities are completed, the Committee has decided to gradually slow the pace of these transactions and anticipates that the full amount will be purchased by the end of October.

Labels: economics, Federal Reserve, forecasting

Monday, June 15, 2009

Not all forecasters are alike

"No one realized how bad the economy was. The projections, in fact, turned out to be worse. But we took the mainstream model as to what we thought -- and everyone else thought -- the unemployment rate would be."

"Everyone guessed wrong at the time the estimate was made about what the state of the economy was at the moment this was passed."Two things about that: First, we were forecasting in a period where there was little good past experience to work form. Almost all forecasting involves taking a set of data that you think represents the state of the economy, looking at the most recent experience and finding "comparable" periods of history where the same conditions essentially occurred. Now of course the data is never identical -- we don't live in test tubes. I refer to macroeconomic data as "in the wild", impure, contaminated by hundreds of other influences that we never measure. You assume the stuff you're not measuring isn't important. Good emphasis on this comes from Ed Leamer, whose book "Macroeconomic Patterns and Stories" includes this paragraph:

You may want to substitute the more familiar scientific words �theory and evidence� for �patterns and stories.� Do not do that. With the phrase �theory and evidence� come hidden stow-away after-the-fact myths about how we learn and how much we can learn. The words �theory and evidence� suggest an incessant march toward a level of scientific certitude that cannot be attained in the study of the com plex self-organizing human system that we call the economy. The words �patterns and stories� much more accurately convey our level of knowledge, now, and in the future as well. It is literature, not science.This was the essence of what I was trying to say Thursday. We try to express that lack of certitude by providing a confidence interval, which when done properly makes most of the so-called "created or saved" jobs into something that could well be just noise. �But even confidence intervals give the forecast a patina of scientism that has no business in economic forecasting. �I'm not confident of confidence intervals (in short, here's a one sentence explanation: I have to have some degree of knowledge of the shape of the distribution of the errors I make in forecasting ... and I question whether or not I can possibly know that.) �When Biden also said�""The bottom line is that jobs are being created that would not have been there before" or that it "clearly has had an impact", we have to respond that we don't know that.

Labels: Biden, economics, forecasting, Obama

Thursday, July 17, 2008

Making new numbers

A lower index number means it's more difficult to find a job because job seekers are facing less demand, or more competition, or both.OK, that sounds very cool to me, as someone who has created some indexes himself for the St. Cloud area. So I'm eager to dig into this index and see what it is and how it works. And they give me details.

The Job Pain Index incorporates measures of supply and demand for workers, and total employment, the point at which supply and demand reach equilibrium.I don't understand the last item. We don't really know what equilibrium employment is; what we observe in the labor market is where the amount of labor sold equals the amount of labor bought, which is true tautologically. We have some idea of full employment unemployment rates (I know, it sounds oxymoronic, but all labor markets will contain some workers who are literally between jobs and others for whom the skill-position mismatch is so severe that they cannot find meaningful work even at full employment. c.f. Greg Ip.) I would think conceptually that an indication of job pain would be measured by things which increase the supply of labor -- meaning workers face more competition from other workers -- or a decrease in the demand for labor -- fewer buyers.

The index contains four items:

- The monthly number of initial claims for unemployment insurance for permanent layoffs (a measure of demand for labor)

- The Conference Board Help-Wanted OnLine Data Series� for Minnesota (another measure of demand)

- The total number of unemployed in Minnesota (a measure of supply)

- The monthly change in total nonfarm employment (seasonally adjusted) in Minnesota (the point at which supply and demand meet)

Help wanted is also a good measure that we use for St. Cloud (our measure comes from linage at the St. Cloud Times rather than an on-line series.) But this is a demand measure that rises when demand is rising, in which case job pain is falling. Perhaps they invert or flip the sign on this number; if not, it points in the opposite direction of job pain.

But an online series is rather skewed in its representation of jobs. Dave Senf at DEED studied online job postings. He finds, for example, that more than 35% of jobs advertised online are professional positions, but the share of professional jobs in the state is closer to 12%. Another 29% of ads online are in management, which is far less than 10% of the jobs out there. We have intentionally kept the newspaper data in St. Cloud because the shares of those jobs in St. Cloud are even less than for the Twin Cities. I think the measure is rather skewed.

I have fewer issues with the number of workers unemployed here, but we do know that workers may be encouraged to join the labor force and leave family-building and other non-labor activities when wages rise. That is not necessarily a measure of pain. But the logic of the index seems to equate pain with an increasing labor surplus. If that's the theory, the component is at least reasonable.

So two of the four items in the index are really suspect, one is good and the other OK if you buy the premise of the index. There already exists a series for each of the fifty states, created by the Philadelphia Federal Reserve, which includes some of the indicators they are using, except rather than some value-laden term like "job pain" they call the index a neutral "coincident indicator" series. The data and methodology are documented there far better than the MPR series, and if one is looking for a piece of data to use I would recommend the Philly series.

About the rest of the Minnesota Slowdown project: I like the idea of the story, but note that it did not include any "economic lookouts" from Central Minnesota. This happens to be the one area that has faster employment and population growth longer-term than the Twin Cities. But the whole project seems to hinge on a story that makes the housing industry's misfortunes cause the state economy to sink before the national economic slowdown/recession. It's the premise the state's economists have used for a year now; weird that with so much pain the government keeps getting more revenue than they expect, isn't it?

Labels: economics, forecasting

Monday, July 14, 2008

Oh no, it's coming! Believe us, it's coming!

On January 15, Tom Stinson, Minnesota state economist, said there was no doubt the state was in a recession. In May, he had not changed his mind. On that basis the state issued a forecast for the budget that led to the closing of a tax loophole, a few minor spending cuts, and the rest of the money coming from reserve accounts. As Phil Krinkie pointed out last month, there was very little spending cuts. I had argued for more reliance on the reserve because I had suggested the recession forecast in the budget report might be more pessimistic than real.

I love it when I turn out to be right.

Minnesota�s net general fund receipts for FY 2008 are now estimated to total $16.257 billion, $389 million (2.5 percent) more than forecast in February. The individual income tax and the corporate income tax accounted for more than 75 percent of the positive revenue variance.They got more money than they expected on 2007 individual income taxes. But lest you be cheery, the state forecasters are not backing off their doom and gloom:

Thus far the U.S. economy has been stronger than was projected at the start of the year. Unfortunately, the good news ends there. Economists now see few signs that economic growth will return to its 3 percent, trend level before mid-2009. Energy prices have increased to levels well beyond those previously projected, housing markets remain severely depressed, and the financial sector�s problems have yet to be fully resolved. The current economic weakness is now expected to extend into early 2009.The forecasters in the WSJ Economic Forecasting Survey don't project 3% on average, but the slowest growth rate forecasted is for Q4 at 0.6%. 2% growth is projected for 2009:II. Global Insights, the vendor that sells its forecast to the Department of Finance, has the most negative number in the forecast for that fourth quarter, at -1.7% (and -0.7% versus an average of +1.3% for 2009:I; it anticipates a sharp bounceback in 2009:II to 2.5% growth.) That is, the Minnesota Department of Finance is basing its forecast for the state budget on a recession call beginning in the fourth quarter, nine months after the initial Stinson statement.

Households received their stimulus package rebate checks ahead of schedule, but that simply shifted some rebate-related spending from the third and fourth quarters of this year into May and June. Accelerating payment of the rebates helped second quarter growth, but it also reduced the amount available for the remainder of the year.

I've certainly bunged up my share of forecasts before, and it's not like GI or Stinson were alone in their recession call. And it's quite possible they're right this time -- I've thought for awhile that the fourth quarter is the key to whether we skirt the recession or not. But the new report lacks some humility in calling for a new recession based on higher oil prices. We have had increased oil prices in percentage terms that like that in the past; why does it matter so this time?

Labels: economics, forecasting, Minnesota

Wednesday, January 16, 2008

A kind word for a state economist

"Tom Stinson tends to be a bit on the pessimistic side of things, to put it charitably," Gov. Pawlenty says.

Pawlenty says governors around the country have shared their concerns about the economic challenges facing Americans. But he says it's important to guard against too much pessimism.

"The economy is deeply challenged, nationally and in Minnesota. But I don't think it's helpful - unless it's clearly justified by the data - for people to get overly pessimistic or overly scare people, either," says Gov. Pawlenty.

With all due respect to Governor Pawlenty, what is a state economist's job? As we've noted, there is not anyone else in a position to speak about the state of the state economy; nobody is going to come along and verify state business cycle peaks and troughs. (I wanted to use the word "officially", but does that word apply to the status of the NBER in dating national cycle peaks and troughs?) I will at some point use the Owyang, Piger and Wall method to date the state cycle (and St. Cloud's) but nobody will say anything about it because, well, it's just me, some economist at Somewhere State. Not A State Economist.

When we published the previous (Fall) report on the state of the economy and reported that our first signal of recession from our new model had flashed, most of the reaction was positive. (There are a few local people who, because they are promoters of St. Cloud business, will not agree with us. We agree to be friendly in our disagreement.) People appreciated someone putting together the case for why the economy may do well or not. And I think that's the reaction we have to this recession call. Glad to hear him say it because he deserves our respect, but I wish I had more background.

Stinson's "pessimism" is largely confined to tamping down revenue expectations so that not too much money is spent by government. (If they do overspend because the revenues didn't pan out, who do you think gets blamed?) Whenever the state budget shows surplus there is a temptation for legislators and governors to spend it on those things that help assure re-election; I think it may fall to someone like a state economist to point out the possibility that the forecast will be in error. You may in fact lean on the scales just a bit. But he has no such incentive that I can see with the recession call. I have to assume it's an honest assessment of the data -- and again, you have to assume he has access to more than we do. I'm trying to reslice the data available to see if I can figure out what he is seeing. So far, I haven't found the right slice, or the right data.

Labels: economics, forecasting, Minnesota

Monday, June 04, 2007

Forecasting decisions versus events

One type of forecasting is forecasting of an event. The revenues generated by the tax code are the result of an event -- what happens in the economy -- multiplied by a vector of tax rates that collect revenue based on a matrix of flows of income and stocks of wealth or assets in the hands of economic agents. The tax rates are constant; the movement in tax bases comes from the Global Insights forecast (as I mentioned earlier). Insert the numbers from that economic forecast in the matrix, plug and chug, and there you are, a revenue forecast.

What I said on the air was that you can't forecast decisions. That's not right exactly; there's a very good example of decision-forecasting in the Taylor Rule, which is a forecast of the Federal Funds rate target set by the Federal Reserve as the basis of its monetary policy. It is a description of how monetary policy was being set under the leadership of Chairman Greenspan. (Does it describe Chairman Bernanke? Look at the graph and decide for yourself. The Taylor Rule, properly understood, is not a mechanism that predicts an economic event but a heuristic used to try to understand how the FOMC is deciding policy at that point in time. The rule is not independent of the committee whose behavior it is forecasting.

Legislatures and executives do not automatically adjust spending to inflation. The budget forecast provided, as noted by the House Fiscal Analysis Department, is the budget's structural balance, i.e., "how much more is being collected than spent before any tax or spending decisions are made." (Emphasis added.) They may do so as an element of policy; the budget forecast provides information on what additional spending would occur if all non-indexed items were to be raised by inflation as measured by CPI. But is it appropriate for an arm of the executive branch to forecast a policy decision of the legislative branch? I think it is not.

There is, by the way, a very simple solution. The Federal government has both an Office of Management and Budget (reporting to the executive branch) and a Congressional Budget Office. If the DFL wants a forecasting arm that reports budget figures the way they would like to read them, have the Senate and House Fiscal Analysis Department provide you that information. What the DFL is doing instead is censoring the information the Finance Department can provide, but not allowing it to report spending without inflation. This is a bad policy.

Labels: economics, Final Word, forecasting, inflation, legislature, Minnesota