Monday, September 08, 2008

FredFan and fiscal dominance

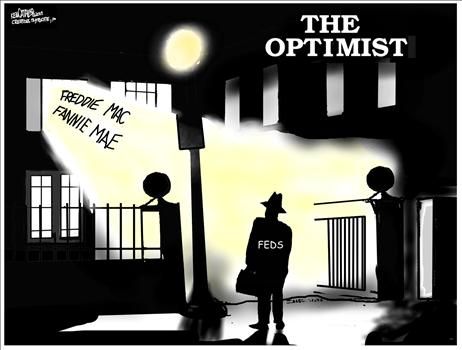

The nationalization of Fannie and Freddie (see Yves Smith for a good overview of the plan) is simply the recognition of something true since the 1980s: The ability of the private owners to exercise a put option on the U.S. government was an important part of the price of its assets. And the only way to prove that the option was there was to have the option exercised.

There were of course many outside pressures brought to bear on the decision: Chinese bondholders; banks that had preferred stock as part of their capital; the elections. Already, Wells Fargo is announcing a substantial writedown of its investments in Fannie and Freddie preferred stock. �But it puts a number of things at peril, and the one I think is going unnoticed is the pressure placed on the Federal Reserve. In short, we seem to be approaching a point where "fiscal dominance" may hinder the independence of the Federal Reserve. This was foreseen by Guillermo Calvo last March in the aftermath of cleaning up Bear Stearns:

...the present situation suggests that central banks may be about to lose the awesome power that they enjoyed during the Great Moderation. The reason is that central banks are beginning to venture into areas that go beyond standard liquidity management by acquiring assets, some of which could be insolvent or require major rescheduling. These are fiscal operations that might tend to deteriorate the already weak US fiscal stance, for instance. In other words, the fiscal anchor may become much weaker than it used to be, bringing about the specter of �fiscal dominance,� a phenomenon that has wreaked havoc in several developing economies.

...[O]ne of the casualties of poor financial regulation may be a weakening of the central banks� ability to anchor nominal prices. In the short run this may be less noticeable in broad price indexes like the CPI but, in my view, it is already being reflected in, for instance, the dollar/euro exchange rate. Under weak nominal anchoring, market-determined exchange rates could become highly volatile because slight changes in moods or expectations may cause them to veer into wildly different directions. And the solution cannot be found in more sophisticated or better regulated derivatives. Derivatives, if anything, make nominal anchoring even more difficult to achieve.

It will be easy to pillory Bernanke, and I don't consider him blameless. �The problem, though, is a philosophy that treats home ownership as everywhere and always a good thing, regardless of the financial condition and literacy of the home owner. �While those who own homes and can still make their payments might not see a fall of more than 5% in their value, there are still lots of loans due to reprice that will wipe out more value (Daniel Alpert puts the overall number at 10% more price decline from here, and a resulting $1.4 trillion in lost home value.) �But the encouragement of risk in homeowning has propelled the fragility that now leads to bailout. �

And this has put the price stability that two recessions and twenty years of attention to credibility at risk. �It seems to me that this was warned about, if you believe his statements, by none other than Alan Greenspan. His memoir notes opposition to Fan and Fred back to 2002, at which time the Fed stopped buying GSE bonds. Also instructive is this retrospective from the Economist. �

The Fed itself could do more to ensure that its eventual mix of duties does not interfere with its commitment to price stability. Mr Bernanke has long said a numerical inflation target would be a safeguard of the Fed�s independence: sacrificing the target to other priorities would demand explanation. When some colleagues balked at a target, he agreed to a compromise: policymakers would publish three-year economic forecasts, and their third-year inflation number would be a proxy target.�

But the system is already showing its weaknesses. The energy-price shock forced officials to raise the third-year inflation forecast by a tenth of a percentage point in June, with none of the public debate a change in a target would have entailed. Frederic Mishkin, who is stepping down as a governor on August 31st, said recently that the Fed should publish forecasts for five or more years to make their preferred inflation rate more explicit and harder to abandon.

Seems the least they could do.

Labels: economics, Federal Reserve